It is safe to say most people have at least a passing knowledge of who Superman is. But Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created and worked on many, many other characters that never reached Superman’s level of fame. (You can probably count on one hand the number of fictional characters that have reached Superman’s level of fame.)

Since a lot of folks reading this blog might be new to their non-Superman works, and we’ll hopefully be talking a lot about and referencing these features as the blog continues, I thought it might be a good idea to give a run-down of the who’s, what’s and where’s of the various features — a basic primer, if you will.

You can’t tell the players without a scorecard, after all.

Where possible, I’ll also be linking to scans of the Who’s Who entries for the characters. Some features created by or worked on by the guys didn’t get entries, but many did. Bear in mind, in most cases, some things talked about in the scans are developments from long after Siegel and Shuster left the company. (Who’s Who: The Definitive Directory of the DC Universe was published in the mid-’80s, well into a period when creators were mining and reviving Golden Age gems as a way of paying tribute to the past.) However, even though they may talk about things beyond Siegel and Shuster, it also helps give a bit of perspective on the legacy and far-reaching impact of their creations.

(By the way, if you’re interested in learning more about the Who’s Who series, don’t miss a series of special episodes of the Fire and Water Podcast, hosted by Rob Kelly of Aquaman Shrine and Shag of Firestorm Fan, doing an issue-by-issue look at the series.)

While this isn’t meant to be a comprehensive list of the characters worked on by Siegel and/or Shuster — I’ll instead just be focusing on ones where they had a hand in the creation — because of the number involved, I’ll be splitting this into two parts. This time out, we’re looking at some of the main features co-created Siegel and Shuster, starting at the very beginning.

Henri Duval bears the distinction of being one of the first two features created by Siegel and Shuster to be professionally published. He and Doctor Occult both appeared in NEW FUN #6 (October 1935 cover date), not just the sixth issue of the title but only the sixth comic published by the company that would eventually become DC Comics. The feature was a period strip featuring the swashbuckling adventures of Henri Duval — famed soldier of fortune — in 17th-century France.

Henri Duval bears the distinction of being one of the first two features created by Siegel and Shuster to be professionally published. He and Doctor Occult both appeared in NEW FUN #6 (October 1935 cover date), not just the sixth issue of the title but only the sixth comic published by the company that would eventually become DC Comics. The feature was a period strip featuring the swashbuckling adventures of Henri Duval — famed soldier of fortune — in 17th-century France.

Unfortunately, Henri Duval was also the shortest-lived feature from the pair, lasting only five one-page installments, and ending abruptly mid-story. (Curiously, the final installment was credited to the pen name of “Hugh Langley,” though unmistakably the work of Siegel and Shuster.) The character has not been used since.

Also debuting in NEW FUN #6, this Siegel-written and Shuster-illustrated strip was, for most of its installments, credited to the pen-names of “Leger and Reuths.” Doctor Occult was a supernatural detective, who, along with his Girl Friday, Rose Psychic, battled vampires, werewolves, ghosts and the undead, long before it was cool. Doctor Occult was considerably more popular than Henri Duval, growing in size from one-page to four-page stories and running monthly installments in the magazine, which was retitled MORE FUN and then MORE FUN COMICS, through the June 1938 cover-dated issue (perhaps only coincidentally, the same month Superman debuted).

Also debuting in NEW FUN #6, this Siegel-written and Shuster-illustrated strip was, for most of its installments, credited to the pen-names of “Leger and Reuths.” Doctor Occult was a supernatural detective, who, along with his Girl Friday, Rose Psychic, battled vampires, werewolves, ghosts and the undead, long before it was cool. Doctor Occult was considerably more popular than Henri Duval, growing in size from one-page to four-page stories and running monthly installments in the magazine, which was retitled MORE FUN and then MORE FUN COMICS, through the June 1938 cover-dated issue (perhaps only coincidentally, the same month Superman debuted).

The character was revived by writer Roy Thomas in the pages off ALL-STAR SQUADRON in 1985, and has made fairly regular appearances in a variety of stories ever since. (Doctor Occult’s entry from WHO’S WHO #6)

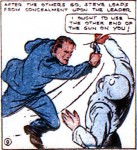

After dabbling in the genres of period adventure and the supernatural, Siegel and Shuster dove into the ever-popular crime detective genre with issue two (January 1936 cover date) of NEW COMICS (later NEW ADVENTURE COMICS and, finally, ADVENTURE COMICS). Federal Men told the adventures of FBI Agent Steve Carson and his G-men. The strip started out with a fairly standard detective story involving a kidnapped child, but quickly became a highly entertaining strip as both Siegel and Shuster stretched their muscles, incorporating a variety of increasingly science-fiction-style elements and visuals, including hidden empires, unknown cities, giant robots and tanks smashing their way through the city, tales of the Federal Men of the future and more. Around mid- to late-1939, as the war began heating up overseas, things settled into less-fantastic stories of spies and espionage, counterfeiting rings and kidnappings.

After dabbling in the genres of period adventure and the supernatural, Siegel and Shuster dove into the ever-popular crime detective genre with issue two (January 1936 cover date) of NEW COMICS (later NEW ADVENTURE COMICS and, finally, ADVENTURE COMICS). Federal Men told the adventures of FBI Agent Steve Carson and his G-men. The strip started out with a fairly standard detective story involving a kidnapped child, but quickly became a highly entertaining strip as both Siegel and Shuster stretched their muscles, incorporating a variety of increasingly science-fiction-style elements and visuals, including hidden empires, unknown cities, giant robots and tanks smashing their way through the city, tales of the Federal Men of the future and more. Around mid- to late-1939, as the war began heating up overseas, things settled into less-fantastic stories of spies and espionage, counterfeiting rings and kidnappings.

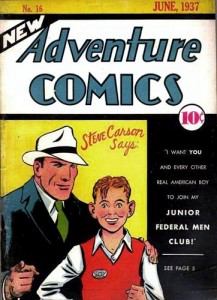

Federal Men holds a special place in the work of Siegel and Shuster as it is the first to be featured on the cover of an issue. NEW ADVENTURE COMICS #16 (June 1937 cover date), also the first issue of the magazine to directly reference a feature inside, promotes the Federal Men strip and the Junior Federal Men Club, the latter of which debuted that issue and was similar to the popular Supermen of America Club that would start two years later in 1939. The cover was likely illustrated by Creig Flessel, not Shuster, but, at that time, to have a feature so prominently promoted on a cover, which were typically generic genre images, was quite an accomplishment.

Siegel is believed to have bowed out of writing duties on Federal Men between the end of 1940 and mid-1941, a period when he stopped writing a number of strips in order to give more attention to Superman. The strip continued for a few more months, through the end of 1941. Neither the strip or Carson have been used since.

Although it was titled Calling All Cars for the first eight installments, Radio Squad debuted in MORE FUN COMICS #11 (July 1936 cover date). I’ve never discovered exactly why the strip’s name was changed, but I suspect it was to avoid confusion with “Calling All Cars,” a popular true-crime radio program that ran from 1933 to 1939.

Although it was titled Calling All Cars for the first eight installments, Radio Squad debuted in MORE FUN COMICS #11 (July 1936 cover date). I’ve never discovered exactly why the strip’s name was changed, but I suspect it was to avoid confusion with “Calling All Cars,” a popular true-crime radio program that ran from 1933 to 1939.

Radio Squad told the adventures of Sandy Keane, square-jawed police patrolman. He was, at times, aided by a partner or sidekick-type character, most often fellow officer Jimmy Trent (later called Larry Trent). The stories were initially two pages in length and were more grounded and lighter in tone than the concurrently running “Federal Men.” Beginning with MORE FUN COMICS #33 (July 1938 cover date), the strip expanded to six-page stories and took on a more consistently serious tone, though remained grounded in a realistic, non-science-fiction world, typically dealing with street-level criminals and thugs.

Similar to Federal Men, Siegel stopped writing the strip in mid-1941. Radio Squad lasted a bit longer after Siegel’s departure, however, with the final installment running at the end of 1942. None of the Radio Squad characters have been used since.

DETECTIVE COMICS #1 (March 1937 cover date) saw the debut of two new features from Siegel and Shuster. The first of these was Spy, which starred Bart Regan, an agent of international espionage, and, at least for the first two years, his girlfriend and later fiancée, Sally Norris. The strip started in a four-page format, soon doubled to eight-page installments and eventually settled into six-page stories for the majority of its run. As the strip continued and the war began to heat up overseas, and at home, particularly following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the strip took on a more serious tone and Regan was challenged by an ever-increasing amount of foreign spies, Axis agents and Nazi saboteurs.

DETECTIVE COMICS #1 (March 1937 cover date) saw the debut of two new features from Siegel and Shuster. The first of these was Spy, which starred Bart Regan, an agent of international espionage, and, at least for the first two years, his girlfriend and later fiancée, Sally Norris. The strip started in a four-page format, soon doubled to eight-page installments and eventually settled into six-page stories for the majority of its run. As the strip continued and the war began to heat up overseas, and at home, particularly following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the strip took on a more serious tone and Regan was challenged by an ever-increasing amount of foreign spies, Axis agents and Nazi saboteurs.

Siegel left this strip also in mid-1941. Spy soldiered on, however, eventually coming to a close at the end of 1943. Bart Regan has not appeared since.

Ever ready to let the haymakers fly and bust some criminal head, the appropriately named Slam Bradley also debuted in DETECTIVE COMICS #1. Slam was a two-fisted, no-nonsense private eye who, along with his friend and partner, Shorty Morgan, fought all sorts of opponents from swindlers and racketeers to spies and mobsters. If you were the criminal element and looking for a fight, Slam was never hesitant to oblige. Slam’s adventures were initially 13-page tales; at the time, the longest of Siegel’s creations and the longest in any of the DC books. After about two-and-a-half years, with the magazine’s newest star, Batman, taking over the book, Slam’s stories dropped to 10-page and soon 8-page installments.

Ever ready to let the haymakers fly and bust some criminal head, the appropriately named Slam Bradley also debuted in DETECTIVE COMICS #1. Slam was a two-fisted, no-nonsense private eye who, along with his friend and partner, Shorty Morgan, fought all sorts of opponents from swindlers and racketeers to spies and mobsters. If you were the criminal element and looking for a fight, Slam was never hesitant to oblige. Slam’s adventures were initially 13-page tales; at the time, the longest of Siegel’s creations and the longest in any of the DC books. After about two-and-a-half years, with the magazine’s newest star, Batman, taking over the book, Slam’s stories dropped to 10-page and soon 8-page installments.

Perhaps showing the popularity of the strip, Slam was also featured in both the 1939 and 1940 issues of NEW YORK WORLD’S FAIR COMICS, most assuredly exposing the character’s hard-boiled, pulp-action adventures to a whole new audience.

Like with other features mentioned above, Siegel’s last Slam Bradley story came in mid-1941. The strip was popular, however, and continued through DETECTIVE COMICS #152 (September 1949), making it the longest-running Siegel and Shuster creation other than Superman and second only to Batman as the longest-running feature in DETECTIVE COMICS. That’s not a bad run. Unfortunately, after his strip ended, Slam was rarely seen for many years, making less than a half-dozen appearances until given a revival by writer Ed Brubaker in 2001 in DETECTIVE COMICS and, shortly after, CATWOMAN. Slam continued to appear in CATWOMAN, and was used in a handful of other stories, most recently, as of this writing, appearing in the LEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT online comic. (Slam Bradley’s entry from WHO’S WHO #21)

In addition, other modern-day stories have introduced members of Slam’s family, including a son, Sam, and older brother, Biff.

No run-down of Siegel and Shuster creations would be complete without mention of the Man of Steel. Superman debuted in ACTION COMICS #1 (June 1938 cover date) and detailed the adventures of Superman — the last son of the dead planet Krypton who, as the famous phrase goes, is “faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings at a single bound.” Since most people are familiar with Superman and his history has been and is being well-documented elsewhere, we’ll leave it at that for now.

No run-down of Siegel and Shuster creations would be complete without mention of the Man of Steel. Superman debuted in ACTION COMICS #1 (June 1938 cover date) and detailed the adventures of Superman — the last son of the dead planet Krypton who, as the famous phrase goes, is “faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings at a single bound.” Since most people are familiar with Superman and his history has been and is being well-documented elsewhere, we’ll leave it at that for now.

Siegel wrote all of Superman’s printed adventures, both in comic books and newspaper strips, through at least 1942 and continued writing stories for the character through 1947. He returned in 1959 and wrote stories for the entire Superman line, which by that time had expanded to include Supergirl, Superboy, the Legion of Super-Heroes, Jimmy Olsen and Lois Lane features, until 1966. Superman has remained in continuous publication since his debut and iterations of the character have appeared in virtually all forms of media. (Earth-Two Superman’s entry from WHO’S WHO #22 and post-Crisis Superman’s entry from the same issue.)

And that’s where we’ll leave off for now. We’ll wrap up in the next installment, where we’ll look at the final Siegel/Shuster co-creation(s) and a half-dozen features created by Jerry Siegel with other artists, including Siegel’s most-famous creation not from Krypton.